Missing Middle Housing: A Micro-Analysis from Andersonville, Chicago

Author: Katlyn Cotton

May 28, 2021

May 28, 2021 | Alyssa Frystak

Last week, as I was walking around my Andersonville neighborhood in Chicago, I noticed the above scene. These three buildings–a 3-unit apartment building built in 1909, a 5-unit apartment building built c. 1966, and a 3-unit condominium building built in 2018–sit right next to each other. At PlaceEconomics, we argue that older, smaller, densely-built neighborhoods are a critical source of affordable housing across the nation, so I wondered if this microcosm might support our theory about older housing stock and affordability.

These types of buildings–small-scale, 2- to 4-flat buildings–have long been the workhorses of Chicago’s residential housing stock and make up approximately 26% of the City’s residential property types, 90% of which are more than 75 years old. However, Chicago’s flat-type buildings are being torn down at an alarming rate and are being reconstructed at lower rates than any other housing type.*

Nationally, older housing stock plays an important and often overlooked role in providing unsubsidized affordable housing. About 29% of housing units in the country were built pre-1960 and they house around 32.4% of households with incomes below $40,000. Older units are also more likely to be renter occupied.

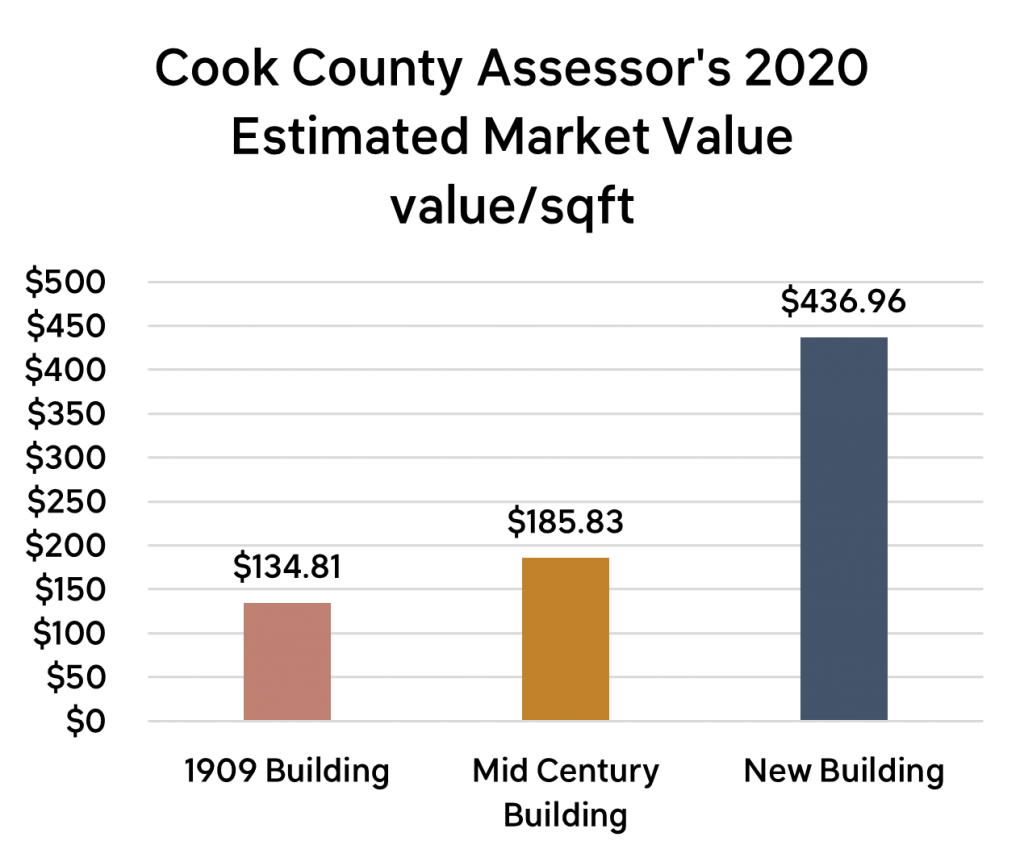

I decided to run some numbers on these three buildings. Using data from the Cook County Assessor’s Office, I found the 2020 estimated market value for each building and calculated the estimated value per square foot.** As demonstrated in the graph below, the value per square foot of the 2018 building is 3 times greater than the 1909 building. This has drastic implications for the future affordability of the neighborhood.

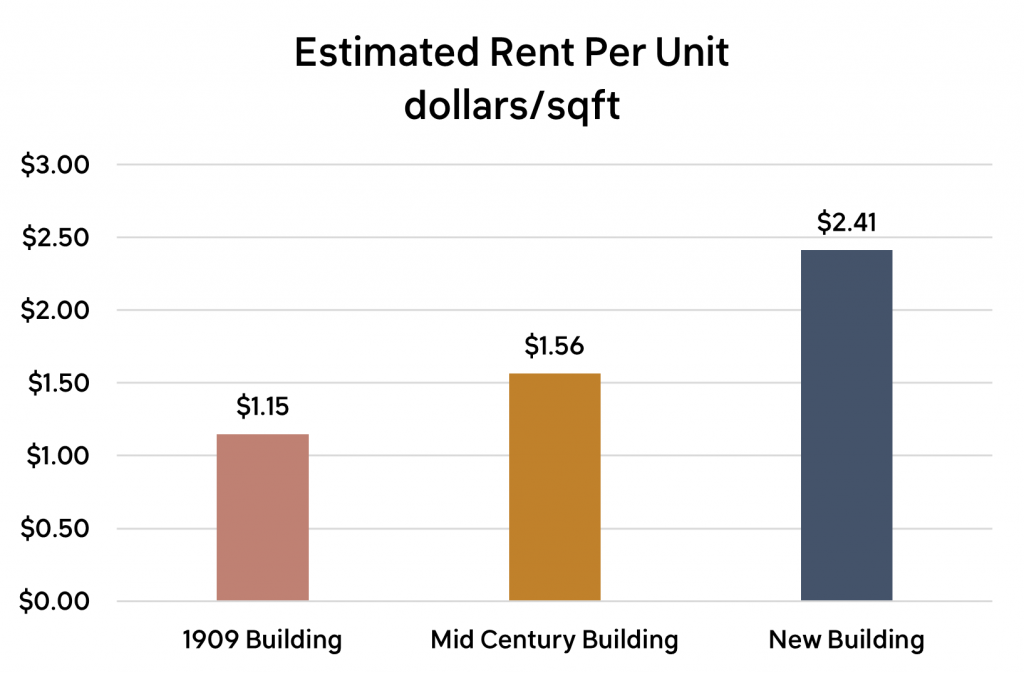

The same pattern emerges when looking at rent levels. Estimated monthly rents for units in these three buildings are as follows: $1950 for a 1,700 sqft unit in the 1909 building, $1250 for an 800 sqft unit in the Midcentury building, and $4100 for a 1,700 sqft unit in the new building. When calculated on a per square basis, the units in the new building rent for twice as much as those in the 1909 building.

Further digging revealed that the new building replaced an older, cottage-style multi-family building of comparable size. We often look at the citywide-level when studying this phenomenon, but it’s useful sometimes to shift the scale. This is just a small vignette and it gives us an understanding of what happens at the block-level when one older residential building is replaced with new construction. But, if we take this one example and extrapolate it across the city, the loss of older, affordable housing represents a significant loss. Over time, if this pattern repeats, it leads to displacement and gentrification that changes the feel of the neighborhood and affects who is able to live there.

During a community engagement session for a recent PlaceEconomics project in Nashville, something that a stakeholder said stuck with me, and probably always will. When talking about tear downs in her neighborhood, she made the observation that once an older, smaller house is lost, that site will never be affordable again. As she put it, “This creates a cycle that is not reversible–it will always be a rich neighborhood from now on.” It’s also important to note that the three buildings used in this micro-analysis don’t fall within the boundaries of an existing historic district, meaning they aren’t protected from demolition and could be torn down and replaced with new construction at any time.

As this micro-analysis illustrates, preservation of older “missing middle” housing is an important way to retain affordability. Unfortunately, land values and existing zoning laws make it virtually impossible to build smaller, affordable multi-family housing without generous subsidies, which makes preserving those that do exist that much more important. As Donovan likes to say, “You can’t build new and rent or sell cheap.”

Missing Middle Housing refers to multi-family or clustered housing types that are compatible with single-family neighborhoods and includes common pre-World War II housing types such as duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, bungalow courts, courtyard buildings, and other small apartment buildings. These tend to be prevalent in older neighborhoods that pre-date existing zoning laws.

Stay tuned for more head to head affordability comparisons from around the country in this “micro-analysis” series.

More Missing Middle Housing resources:

https://missingmiddlehousing.com/the-missing-middle-affordable-housing-solution/

https://nextcity.org/features/view/cities-affordable-housing-design-solution-missing-middle

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lHzTltos8gY&t=567s

* Michael Podgers, “Is There Hope for the Disappearing Chicago Two-flat?” Chicago Curbed, December 21, 2018, accessed January 7, 2019.

** Due to the nature of the available assessment records and the difference in the type of building (apartment versus condominium) being compared, a margin of error is to be expected. For the two older buildings, we calculated the value per square foot using the total square footage and value of the whole building. However, for the new construction example, the value per square foot was calculated using the square footage and estimated market value of only one condo unit.

***

Alyssa Frystak is the Director of Research and Data Analytics at PlaceEconomics. She is a native Chicagoan and enjoys exploring all 77 of the City’s unique neighborhoods.