Let’s Talk About: Deconstruction

Author: Katlyn Cotton

Mar 22, 2021

Over here at PlaceEconomics, we are big fans of deconstruction. It’s encouraging to see more and more cities using it to improve safety, create jobs, and encourage materials reuse. We are excited to share some of the larger takeaways from our latest report for the City of San Antonio, which assesses how a deconstruction ordinance would further the City’s sustainability, economic, and equity goals. You can read the full report here.

Deconstruction – The process of dismantling structures component by component in order to harvest materials to be salvaged.

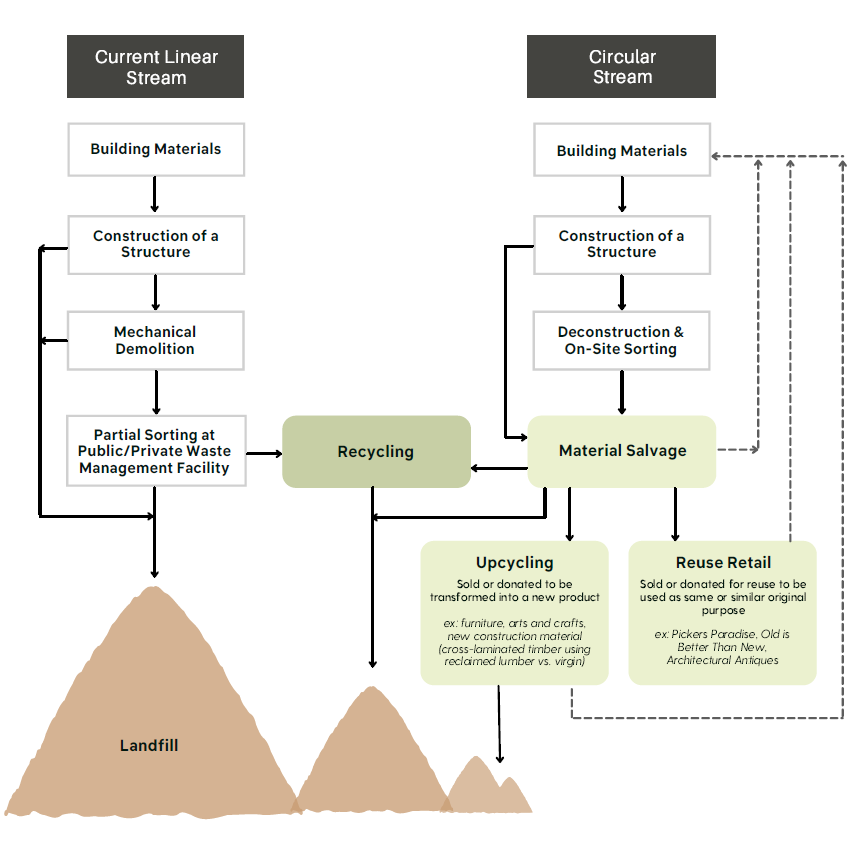

As an alternative to mechanical demolition, deconstruction just makes sense. If a building is going to be demolished, careful deconstruction is a far better outcome than the quick, fast, and wasteful alternative. It creates more jobs, releases fewer harmful pollutants into the environment, and keeps building materials out of landfills while ensuring they can be salvaged and reused. When it comes to the future of historic preservation, deconstruction and materials reuse really should be part of the conversation.

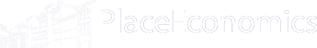

Circular Economy – An economic system where products and services move in closed loops or circles by employing reuse, sharing, refurbishment, recycling, and remanufacturing, with the goal of keeping products in use longer and thus increasing the productivity of a resource.

Deconstruction is a key step in transitioning from a linear economy model, whereby materials are manufactured, used, and discarded, to a circular economy, where rather than discarded, materials are recycled and reused. Encouraging deconstruction allows cities to recover and leverage existing assets, while helping meet stated economic, equity, sustainability, and housing goals.

It’s important to point out that demolition is more than a preservation issue. Lower-income communities, and often communities of color, are disproportionately impacted by demolition and its harmful side effects. Mechanical demolition releases hazardous particulates into the air that can lead to serious health issues. Though the dispersal of particulates can be mitigated, (spraying water during demolition and collecting and disposing of runoff are best practices) proper precautions are often not practiced or enforced. Lead and other chemical pollutants such as asbestos, mercury, crystalline silica, and arsenic, are disturbed during the process and end up dispersed into the air. They can also make their way into the groundwater supply, where they may contaminate drinking water. In dense urban areas, demolition can also have major implications on adjacent structures. Manual deconstruction is a much safer alternative, all around.

Some may be reluctant to welcome deconstruction into the realm of preservation. Dismantling buildings, however carefully, can feel fundamentally opposed to our core mission as preservationists. But deconstruction definitely deserves a spot in our policy toolkit, especially as we look to ways that we can support sustainability, jobs, and equity. We like to think of deconstruction as a necessary alternative to demolition that can support preservation–not the other way around–through making materials available for restoration projects, extending the life of the embodied energy contained in the extant environment, and keeping communities safer.

We’re encouraged to see that municipalities across the country are beginning to realize the additional environmental, social, and economic benefits that deconstruction offers compared to mechanical demolition. San Jose, CA (2001), Madison, WI (2010), Cook County, IL (2012), Portland, OR (2016), and Palo Alto (2020) have all implemented deconstruction or waste diversion programs. St. Louis, MO, is in the gathering research phase, and Charlotte, NC, has published a broad-reaching effort to pivot to a circular economy.

Though this study looked at the impact of a deconstruction ordinance in San Antonio, many of the findings have national implications. Below are the key takeaways that sold us on deconstruction as an important tool for preservationists:

- Deconstruction ordinances, allow cities to recover and leverage existing buildings and materials to help meet sustainability goals.

- Deconstruction programs spur businesses, create more jobs, and recover valuable building material that can then be made locally available for maintenance and repair of older buildings and homes.

- A recent national survey of the deconstruction industry revealed that the total labor income (direct, indirect and induced) from deconstruction is nearly four times that of demolition.

- Deconstruction presents a huge opportunity for workforce development and job training initiatives.

- Material reuse industries are expected to grow at a faster pace than the U.S. economy as a whole.

- A circular economy offers more employment opportunities. Reuse/refurbishment produces 300 jobs per 10,000 tons of waste compared to 1-6 jobs in the traditional landfilling/incineration process.

- Many strong examples around the country offer precedents to build from: Phoenix started an incubation hub that has had a direct impact on its reuse/refurbishment market over the course of 6 years, including the launch of 19 companies, filing of 14 patents, and development of 15 products.

- Deconstruction supplies quality materials for preservation and restoration projects. There is a demand from homeowners for materials from houses built nearby, which are likely to be similar, allowing nearby property owners to “replace like with like.”

- Mechanical demolition is hazardous to the health of local residents and often disproportionately impacts lower income communities and people of color.

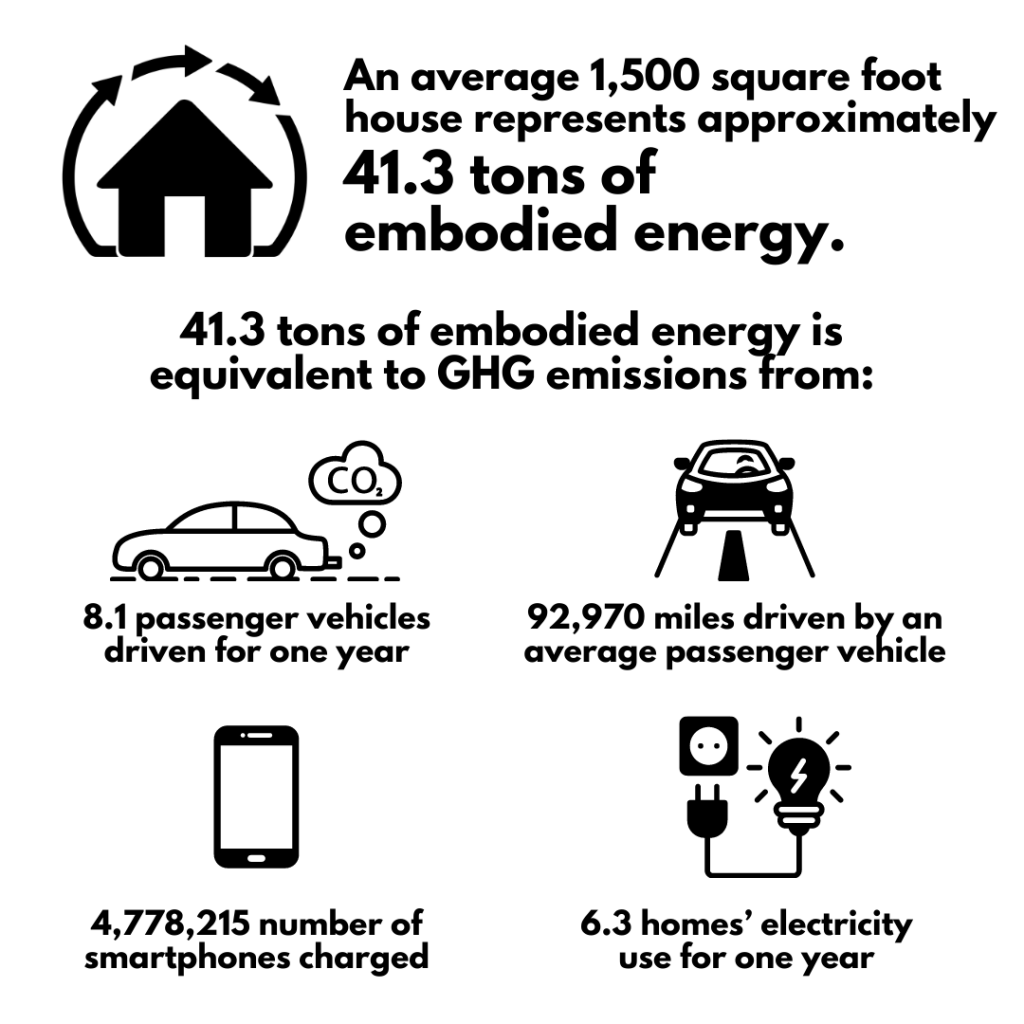

- Deconstruction keeps materials in use. An average 1,500 square foot house represents approximately 41.3 tons of embodied energy.

We’ll be back on the PlaceBlog next week to share some of the creative business models and innovate programs spurred by deconstruction initiatives around the country!